Chemotherapy and molecular targeting therapy for recurrent cervical cancer

Introduction

Secondary to effective cervical cytology screening,cervical cancer incidence has declined by 70% over the last half-century in most developed countries (1). In Japan,cervical cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer and the second most common cause of death among these patients. Moreover,cervical cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide with an annual incidence of 530,000 cases; 250,000 deaths are expected from this largely preventable disease (2). Although early-stage and locally advanced cancers may be cured with radical surgery,chemoradiotherapy,or both,patients with metastatic cancers and those with persistent or recurrent disease after platinum-based chemoradiotherapy have limited options (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17).

In locally advanced cervical cancer,Rose et al. identified prognostic factors by multivariable analysis including histology,race/ethnicity,performance status,tumor size,International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage,tumor grade,pelvic node status,and treatment with concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy (18). For patients with primary stage ⅣB,persistent,or recurrent cervical cancer,chemotherapy remains the standard treatment,although this is neither curative nor associated with long-term disease control (19). The prognosis for advanced or recurrent cervical carcinoma is poor,with a 1-year survival rate between 10% and 15% (20). The need for effective therapy in this clinical setting is well recognized and optimal treatment has yet to be defined.

In this review,we summarized the history of the medical treatment of recurrent cervical cancer,and the current recommendations for chemotherapy and molecular targeted therapy. Eligible articles were identified by a search of MEDLINE bibliographical database for the period up to November 30,2014. The search strategy included any or all of the following keywords: “uterine cervical cancer”,“chemotherapy”,and “targeted therapies”.

Single agent chemotherapy

CDDP

Cisplatin has been the primary chemotherapy for advanced cervical cancer patients. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study included 34 patients with advanced or recurrent cervical squamous cell carcinoma treated with cisplatin 50 mg/m2 every 3 weeks (21). Overall response rate (ORR) was 38%; however,three complete responses (CR) and eight partial responses (PR) were observed in 22 previously untreated patients for an ORR of 50%. Only two PR were observed in 12 patients who had received prior chemotherapy.

Based on antitumor effect,toxicity,and feasibility,a dose of 50 mg/m2 every 21 days became the standard administration method for cisplatin.

Topotecan

Topotecan inhibits topoisomerase-I,an intranuclear enzyme which relieves torsional stress in DNA (22). Binding of topotecan to topoisomerase-I creates a stabilized cleavable complex leading to single-strand DNA breaks,which are converted to lethal double-strand breaks during DNA replication. In addition to these direct effects,topotecan has been shown to potentiate the activity of cisplatin through inhibition of DNA repair (23).

The GOG evaluated the activity and toxicity of topotecan in a multicenter Phase Ⅱ study for patients with previously treated squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix (24). Topotecan was administered at 1.5 mg/m2 per day for 5 consecutive days,on a 21 days cycle. Forty patients were evaluated and the ORR was 12.5% with stable disease (SD) in an additional 37.5%. Median progression free survival (PFS) was 2.1 months. As a single agent topotecan shows modest antitumor activity in patients with previously treated squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. These results led the GOG to include the combination of topotecan and cisplatin in phase Ⅲ trials.

Paclitaxel

A phase Ⅱ trial of paclitaxel was initiated in advanced non-squamous carcinoma of the cervix to determine its activity in patients who had failed standard chemotherapy (25). The starting dose of paclitaxel was 170 mg/m2 (135 mg/m2 for patients with prior pelvic radiation) given as a 24-hour continuous intravenous infusion with courses repeated every 3 weeks. In this trial,42 assessable patients were initially entered onto the study,and 13 responses were seen; 4 patients had a complete response,and 9 patients had a partial response. The ORR was 31%. The primary and dose-limiting toxicity was neutropenia.

The authors concluded that paclitaxel was effective in non-squamous carcinoma of the cervix.

Nab-Paclitaxel

Nab-paclitaxel is a nanoparticle formulation of albumin-bound paclitaxel (26). No premedication is required as the risk of hypersensitivity (27).

GOG conducted a phase Ⅱ trial of nab-paclitaxel in the treatment of recurrent or persistent advanced cervix cancer (28).

Nab-paclitaxel was administered at 125 mg/m2 i.v. over 30 min on day 1,8 and 15,of each 28-day cycle,to 37 women with metastatic or recurrent cervix cancer that had progressed or relapsed following first-line cytotoxic drug treatment. Thirty-five eligible patients were evaluated for response and tolerability. All of the eligible patients had one prior chemotherapy regimen and 27 of them had prior radiation therapy with concomitant cisplatin. The median numbers of nab-paclitaxel cycles were 4 (range,1-15). Ten [28.6%; 95% confidence interval (CI),14.6-46.3%] of the 35 patients had a PR and another 15 patients (42.9%) had SD. The median PFS and overall survival (OS) were 5.0 and 9.4 months,respectively. In fact,the 28.6% ORR in the 35 eligible patients is the highest ever recorded in the GOG for a single-agent against drug refractory,platinum resistant disease (29, 30, 31, 32). Thus,nab-paclitaxel may be considered a leading candidate for future studies of combinations of agents in both adjuvant and advanced disease settings,especially evaluating weekly dosing schedules.

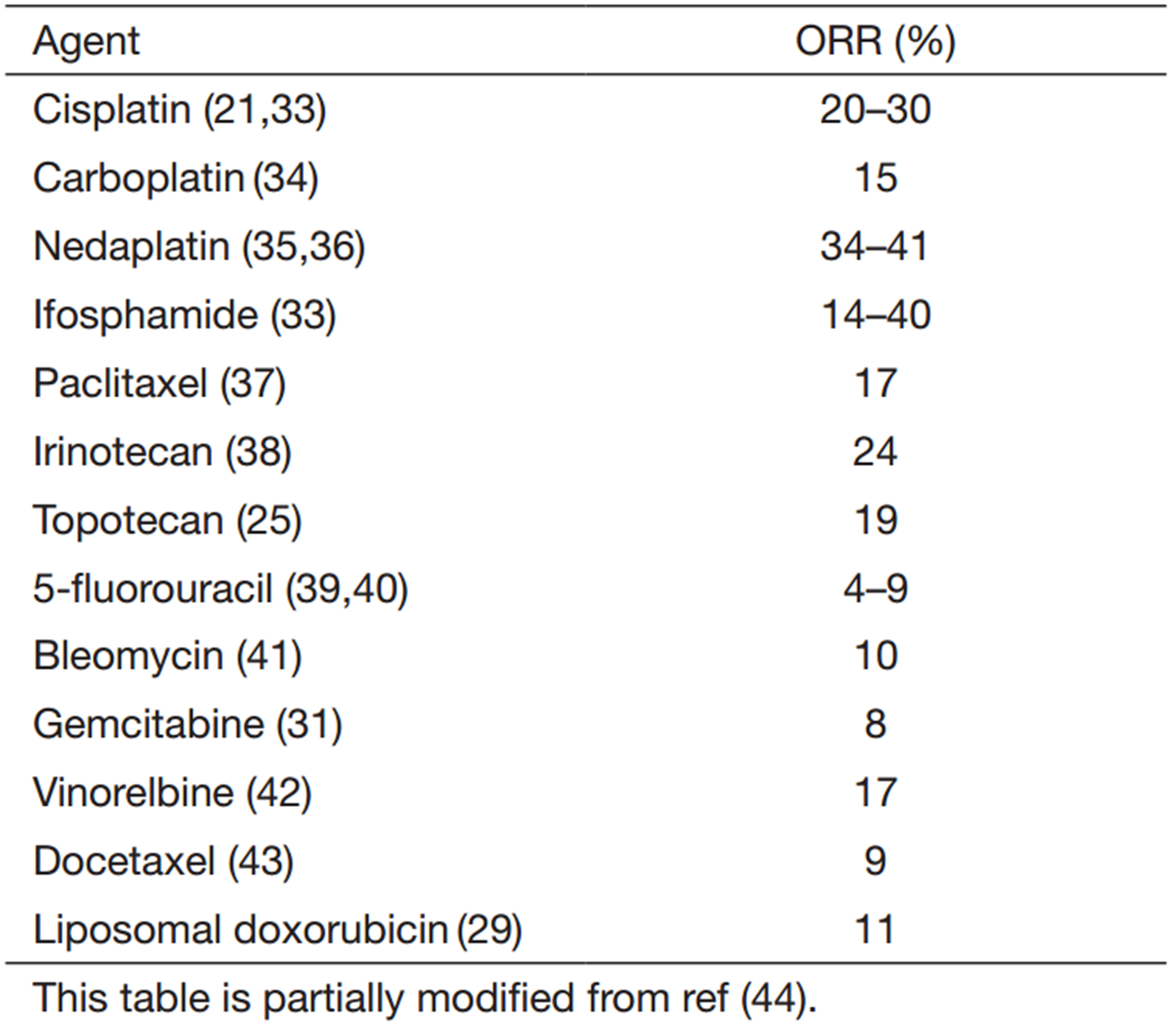

Table 1 shows the results of ORR of single agent chemotherapy.

Full table

Combination chemotherapy: phase Ⅱ clinical trials

In trials of combination chemotherapy,other active agents were selected with cisplatin. Therefore,several agents,which showed modest to good response,were used to test the activity in phase Ⅱ trial combined with cisplatin. Also,cisplatin analogues (CBDCA,nedaplatin) were examined to have response substitution for cisplatin for decreasing the adverse effects of cisplatin.

Topotecan/CDDP

Fiorica and colleagues conducted a phase Ⅱ trial evaluating cisplatin/topotecan in persistent or recurrent cervical cancer patients (45).

A 50 mg/m2 of cisplatin on day 1 and 0.75 mg/m2 of topotecan on day 1,2,and 3 of a 21-day cycle were given for 6 cycles or until disease progression.

Thirty-two of the 35 enrolled patients were evaluated for toxicity and tumor response. All but two evaluable patients had received previous radiotherapy. No patient received prior chemotherapy. The most common toxicity was hematologic,with grade 3 and 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia reported in 30% and 10% of cycles,respectively. The ORR was 28% (9/32),with 3 CR and 6 PR. Nine (28%) patients had SD. The antitumor response in non-irradiated fields (30%) was similar to the response observed in previously irradiated fields (33%),suggesting good drug penetration. Median duration of response was 5 months (range,2 to 15+ months). An additional 9 (28%) patients achieved SD. The median OS was 10 months. The authors concluded that cisplatin/topotecan is safe,well tolerated,and active in cervical cancer patients.

Paclitaxel + CDDP

On the basis of activity of paclitaxel as a single agent in chemotherapy for naive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix in a prior GOG trial,a phase Ⅱ study of paclitaxel and cisplatin,as first-line therapy,was conducted by the GOG (46).

Patients received paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 over 24 h followed by cisplatin 75 mg/m2 every 21 days. A total of 41 patients were evaluable for response. Forty (90.9%) had received prior radiation therapy. Of the 41 assessable patients,5 (12.2%) had CR and 14 (34.1%) had PR for an ORR of 46.3%. The median PFS was 5.4 months with a median OS of 10.0 months (range,0.9-22.2 months). Response was more frequent in patients with disease in non-irradiated sites (70% vs. 23%,P=0.008).

The authors concluded that this regimen seemed highly active and those results led to the development of GOG169 in a phase Ⅲ randomized study,comparing combinations of paclitaxel/cisplatin with cisplatin alone.

Paclitaxel + CBDCA

Patients with advanced or recurrent carcinoma of the cervix were treated with carboplatin/paclitaxel every 28 days (47). Starting doses of carboplatin/paclitaxel were: AUC 5-6 and 155-175 mg/m2.

Twenty-five women treated with this combination were identified. Twenty-three women (92%) had prior treatment with pelvic radiotherapy and 14 (56%) had concurrent radio-sensitizing cisplatin. There was a 20% PR and a 20% CR rate (10/25). The median PFS for the entire group was 3 months.

The median OS was 21 months. The authors concluded that carboplatin/paclitaxel was an active combination in advance and recurrent cervical cancer.

Paclitaxel + nedaplatin

Nedaplatin (cis-diammine glycolato platinum) is a cisplatin analogue which was developed as a less nephrotoxic agent in Japan in 1995.

A multicenter phase Ⅱ trial was conducted to evaluate activity and toxicity of paclitaxel/nedaplatin in patients with advanced/recurrent uterine cervical cancer. Treatments consisted of paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 over 3 h and nedaplatin 80 mg/m2 intravenously over 1 h on day 1 every 28 days until progressive disease or adverse effects prohibited further therapy.

A total of 45 patients were eligible for assessment of response to treatment; 31 patients (62%) received prior radiotherapy and 23 patients (46%) received prior chemotherapy. The ORR was 44.4% (11 CR and 8 PR) with 22.2% of patients having SD. Non-hematologic toxicity was generally not serious and without dominant pattern. The median PFS was 7.5 months and OS was 15.7 months. Neurotoxicity is one of the main toxicities of cisplatin and paclitaxel. Papadimitriou et al. reported in their phase Ⅱ study with PC therapy (48),53% of their patients developed some degree of neurotoxicity,including grade 3 neurotoxicity in 9% (8). In this study,grade 3 or 4 neurotoxicity occurred in only one patient (2.0%). The authors concluded that paclitaxel/nedaplatin demonstrated easy administration,favorable anti-tumor activity,and the toxicity profile of this regimen could be decreased with cisplatin containing combinations.

Combination chemotherapy: phase Ⅲ clinical trials

As noted 50 mg/m2 cisplatin every 21 days was considered the historical standard treatment for recurrent cervical cancer (21). Subsequent trails evaluated and demonstrated activity for other agents including mitolactol,ifosfamide,paclitaxel,gemcitabine,topotecan and vinorelbine among others (37, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55). Accordingly,promising agents were incorporated into phase Ⅲ trials. In this section,we summarized landmark phase Ⅲ clinical trials conducted by GOG and Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG). Table 2 shows the results of representative phase Ⅲ clinical trials.

Full table

GOG169

Since previous GOG phase Ⅱ trials demonstrated paclitaxel/cisplatin combination seemed highly active in cervical cancer,a phase Ⅲ trial compared paclitaxel/cisplatin with cisplatin alone (14).

Among 264 eligible patients,134 received cisplatin and 130 received cisplatin/paclitaxel. The majority of all patients had prior radiation therapy (cisplatin,92%; cisplatin/paclitaxel,91%). ORR was 19% (6% CR plus 13% PR) of patients receiving cisplatin vs. 36% (15% CR plus 21% PR) receiving cisplatin/paclitaxel (P=0.002). The median PFS was 2.8 and 4.8 months,respectively,for cisplatin vs. cisplatin/paclitaxel (P<0.001). There was no difference in median OS (8.8 vs. 9.7 months). Importantly,this trial prospectively collected quality of life (QOL) assessment data before each treatment cycle. Although the QOL scores were similar for both groups,the dropout rate,as determined by completion of the survey,was higher in the cisplatin group,suggesting stable QOL rather than worsening QOL for patients receiving combination therapy. The authors concluded cisplatin/paclitaxel is superior to cisplatin alone with respect to response rate and PFS with sustained QOL.

GOG179

Following GOG169 closure,a replacement trial compared single agent cisplatin to other active regimens from previous phase Ⅱ trials. Patients were randomized into one of three treatment arms: (Ⅰ) cisplatin (Ⅱ) cisplatin/topotecan and (Ⅲ) methotrexate,vinblastine,doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC) (15). The MVAC arm was closed by the Data Safety Monitoring Board after four treatment-related deaths occurred among 63 patients,and was not included in this analysis. Among cisplatin vs. cisplatin/topotecan,improvements in ORR (27% vs. 13%; P=0.004),and PFS (4.6 vs. 2.9 months; P=0.014) favored cisplatin/topotecan regimens. OS was higher for the combination regimen compared to single agent cisplatin (9.4 vs. 6.5 months; P=0.017). This was the first randomized phase Ⅲ trial to demonstrate a survival advantage for combination chemotherapy over cisplatin alone,in advanced cervix cancer. The ORR of single agent cisplatin was only 13%. Compared with GOG169,where 30% of patients received chemoradiation on the cisplatin alone control arm,56% of patients on the control arm in GOG179 had been treated with prior chemoradiation therapy,potentially explaining the benefit seen for the experimental arm. Encouraging results for combinations including topotecan and cisplatin improved OS,leading to its addition to GOG204.

GOG204

GOG204 incorporated the winning cisplatin doublets from the two preceding trials,cisplatin/paclitaxel (GOG169) and cisplatin/topotecan (GOG179). Two other combination regimens with gemcitabine/cisplatin and vinorelbine/cisplatin were evaluated in this very important phase Ⅲ trial (5). A total of 513 patients were enrolled prior to a planned interim analysis: 70% of patients had been treated with prior cisplatin chemoradiation. The trial was closed early after the analysis showed that the three control arms were not superior to cisplatin/paclitaxel. The ORR was statistically similar for each of the four arms,ranging from 22.3% for gemcitabine/cisplatin to 29.1% for paclitaxel/cisplatin. While PFS (4-5.8 months) and OS (10-12.9 months) were similar between arms,paclitaxel was noted to have the highest response rate at 29.1% and OS of 12.9 months.

Vinorelbine/cisplatin,gemcitabine/cisplatin,and topotecan/cisplatin are not superior to paclitaxel/cisplatin in terms of OS. However,the trends in ORR,PFS,and OS favor paclitaxel/cisplatin as standard care. This GOG204 represented a significant step forward in defining optional therapy,however,low ORR (29.1%) and relatively short OS (12.9 months) were disappointing. The OS was significantly worse for patients who had undergone previous concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) than for those who had undergone radiotherapy alone [hazard ratio (HR) =1.148; 95% CI,0.90-1.47]. These results suggest that although CCRT contributes to improve prognosis of advanced cervical cancer,treating recurrent disease after CCRT is still difficult because both chemotherapy and radiation therapy have already been administered.

JCOG0505

Patients with recurrent or advanced cervical cancer,however,often have problems in the urinary tract,which can induce renal dysfunction. For such patients,administration of cisplatin was difficult owing to renal toxic effects. Carboplatin,despite being a derivative of cisplatin,was gaining attention because of its low renal toxic effect and no need for hydration.

JCOG conducted a randomized phase Ⅲ study to evaluate clinical benefits of carboplatin/paclitaxel compared with cisplatin/paclitaxel for patients with advanced or recurrent disease.

Of 253 enrolled patients,246 were evaluable,including 201 with disease assessable for response (57). The ORR was 60% for cisplatin/paclitaxel and 62% for carboplatin/paclitaxel. The median OS and PFS were 18.3 and 6.9 months for cisplatin/paclitaxel,and 17.5 and 6.2 months for carboplatin/paclitaxel. Thus,carboplatin/paclitaxel proved comparable with cisplatin/paclitaxel in terms of antitumor activity. Carboplatin/paclitaxel was also less toxic than cisplatin/paclitaxel in inducing febrile neutropenia,creatinine elevation,and nausea/vomiting. Most importantly,interim analysis demonstrated that substitution of carboplatin for cisplatin did not result in inferior outcome. Observed toxicities were similar in severity and frequency based on previous experiences with these compounds.

Interestingly,in secondary analysis of 117 patients who hadn’t received prior platinum,cisplatin/paclitaxel doublet appeared to be superior to carboplatin/paclitaxel with median OS of 23.2 vs. 13.0 months (HR =1.57; 95% CI,1.06-2.32).

Without evidence of inferiority,carboplatin and paclitaxel may become the new standard for patients with recurrent disease,unless they have not received prior chemoradiation therapy,where they may benefit from cisplatin and paclitaxel.

Molecular targeted therapy

Prognosis of patients who recurred after prior chemotherapy are very poor,therefore new therapeutic strategies are urgently required. Molecular targeted therapy will be the most hopeful candidate for these strategies. Compared with other cancer,there are few clinical trials of molecularly targeted agents. However,the results of bevacizumab in therapeutic trials for cervical cancer have shown that targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway is an attractive therapeutic strategy.

In this section,we summarized several molecularly targeted agents,correlating with activated pathways in cervical cancer,like VEGF,epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR).

VEGF pathway

Angiogenesis,the process leading to the formation of new blood vessels from a preexisting vascular network,is necessary for tumor growth,invasion,and metastasis. Angiogenesis is critical in tumor growth and survival and has been generally considered a very attractive target for cancer therapy. VEGF plays a pivotal role in the control of angiogenesis,tumor growth and metastasis (59, 60, 61). The binding of VEGF to its receptors activates a signaling cascade that ultimately produces increased endothelial cell survival,proliferation,vascular permeability,migration and invasion (62). Cervical cancer is heavily dependent on angiogenesis,perhaps even more than most solid tumors,because human papillomavirus infection and ongoing hypoxia (associated with increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha) are associated with increased levels of VEGF,a common target for anti-angiogenesis therapy. Overexpression of VEGF has been associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in several tumors,including cervical cancer (63). Cytosol protein level of VEGF has been shown to be increased in cervical cancer compared to normal cervical tissue (64, 65, 66, 67). Monoclonal antibodies,like bevacizumab and small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs),like pazopanib are hopeful candidates in specific treatments against VEGF.

Bevacizumab

Bevacizumab (Avastin®,Genentech) is a humanized antibody that recognizes and neutralizes all major isoforms of VEGF,preventing receptor binding and inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation and vessel formation (68). Bevacizumab was the first FDA-approved therapy designed to inhibit angiogenesis in patients with advanced colorectal and later non-small lung cancer and renal cancer (69). Bevacizumab targets VEGF-A,which seems increased in malignant cervical cancer cells,as well as correlated with advanced stage of cervical cancer (70). A phase Ⅱ multicenter trial reported a supposedly better PFS (24% probability to survive more than 6 months; 90% CI,14-37%),median OS (7.29 months; 95% CI,6.11-10.41 months),and ORR (10.9%; 90% CI,4.4-21.5%) (32).

GOG240

In GOG240,a phase 3,randomized trial performed in the United States and Spain through GOG and Spanish Research Group for Ovarian Cancer,they investigated the incorporation of bevacizumab and the use of non-platinum combination chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced cervical cancer (56). They randomly assigned 452 patients to chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab at a dose of 15 mg/kg. Chemotherapy consisted of cisplatin at a dose of 50 mg/m2,plus paclitaxel at a dose of 135 or 175 mg/m2 or topotecan at a dose of 0.75 mg/m2 on days 1 to 3,plus paclitaxel at a dose of 175 mg/m2 on day 1. Cycles were repeated every 21 days until disease progression. The majority of patients (72%) had recurrent disease,and 11% had persistent disease. More than 70% in each group had previously received platinum-based chemoradiotherapy.

Topotecan/paclitaxel wasn’t superior to cisplatin/paclitaxel (HR for death =1.20). With the data for the two chemotherapy regimens combined,the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy was associated with increased OS (17.0 vs. 13.3 months; HR for death =0.71; 98% CI,0.54-0.95; P=0.004 in a one-sided test) and higher ORR (48% vs. 36%,P=0.008). Among patients who received bevacizumab,28 had CR,and among those who received chemotherapy alone,14 had CR (P=0.03). Bevacizumab,as compared with chemotherapy alone,was associated with an increased incidence of grade 2 hypertension or higher (25% vs. 2%; P<0.001),grade 3 or higher thromboembolic event (8% vs. 1%; P=0.001),and grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal fistulas (6% vs. 0%; P=0.002). Bevacizumab-containing regimens were associated with reduced hazard of disease progression and increased probability of response. Even when target lesions were located in the previously irradiated pelvis,it appears bevacizumab-containing therapy was effective. The addition of bevacizumab to combination chemotherapy in patients with recurrent,persistent,or metastatic cervical cancer was associated with an improvement of 3.7 months in median OS. GOG240 is a landmark trial because it is the first time a targeted agent has reached its primary endpoint of improving OS in gynecologic cancer.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) updated their practice guidelines for cervical cancer treatment to include the cisplatin-paclitaxel-bavacizumab triplet as a recommended therapy in recurrent and metastatic disease (category 2A).

Anti-VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

Pazopanib

Pazopanib is a potent and selective multi-targeted receptor TKIs of VEGFR-1,VEGFR-2,VEGFR-3,PDGFR-a/®,and c-kit that blocks tumor growth and inhibits angiogenesis. Pazopanib is under clinical development for treatment of multiple tumor types and has been approved for renal cell carcinoma by the FDA (71).

A phase Ⅱ study of pazopanib and lapatinib monotherapy compared with pazopanib plus lapatinib combination therapy in patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer,has demonstrated the benefits of pazopanib (72). Patients with measurable stage ⅣB persistent/recurrent cervical carcinoma not amenable to curative therapy and at least one prior regimen in the metastatic setting were randomly assigned in a ratio of 1:1:1 to pazopanib at 800 mg once daily,lapatinib at 1,500 mg once daily,or lapatinib plus pazopanib combination therapy (lapatinib at 1,000 mg plus pazopanib at 400 mg once daily or lapatinib at 1,500 mg plus pazopanib at 800 mg once daily).

The futility boundary was crossed at the planned interim analysis for combination therapy compared with lapatinib therapy,and the combination was discontinued.

Pazopanib improved PFS (HR =0.66; 90% CI,0.48-0.91; P=0.013). Median OS was 49.7 and 44.1 weeks (HR =0.96; 90% CI,0.71-1.30; P=0.407) and ORR were 9% and 5% for pazopanib and lapatinib,respectively (73). The only grade 3 adverse effects >10% was diarrhea (11% pazopanib and 13% lapatinib). Grade 4 adverse effects were reported at 9% (lapatinib) and 12% (pazopanib). This study confirmed the activity of anti-angiogenesis agents in advanced and recurrent cervical cancer and demonstrates the benefits of pazopanib based on the prolonged PFS and favorable toxicity profile.

EGFR pathway

Anti-EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

EGFR is composed of an extra cellular ligand-binding domain,a transmembrane lipophilic segment,and an intracellular protein kinase domain with a regulatory carboxyl terminal segment. On binding of ligand,EGFR dimerization occurs,resulting in high-affinity ligand binding,activation of the intrinsic protein tyrosine kinase activity,and tyrosine auto-phosphorylation. The EGFR was the first identified of a family of receptors known as the EGFR family or ErbB tyrosine kinase receptors. This receptor family is comprised of four homologue receptors; EGFR itself (ErbB1/EGFR/HER1),ErbB2 (HER2/neu),ErbB3 (HER3),and ErbB4 (HER4). The rationale for targeting the EGFR family for cancer therapy is compelling. These receptors are frequently overexpressed in human tumors,correlating with a more aggressive clinical course (74).

TKIs are a class of orally available and small molecules that inhibit ATP binding within the TK domain,leading to compare inhibition of EGFR auto-phosphorylation and signal transduction (75). Gefitinib is TKIs against EGFR,which have been evaluated as single agents in patients with cervical cancer.

Gefitinib

Gefitinib (ZD1839,Iressa®,AsteraZeneca Pharmaceuticals) has been approved by the FDA for treatment of platinum- and docetaxel- refractory non-small-cell lung cancer (76).

A multicenter phase Ⅱ trial evaluated the clinical outcomes of 28 recurrent cervical cancers treated with 500 mg/day gefitinib. The exploratory objective was to investigate the correlation of baseline EGFR expression with tumor response and disease control.

Although there were no objective responses,6 (20%) patients experienced SD with a median duration of 111.5 days. Median time to progression was 37 days and median OS was 107 days. Disease control did not appear to correlate with levels of EGFR expression. Gefitinib was well tolerated,with the most common drug-related adverse events being skin and gastrointestinal toxicities. Gefitinib has only minimal monotherapy activity. However,the observation that 20% of patients treated with gefitinib had SD may warrant further investigation (77).

mTOR pathway

The mTOR is a key protein kinase controlling signal transduction from various growth factors and upstream proteins to the level of mRNA and ribosome with regulatory effect on cell cycle progression,cellular proliferation and growth. In various diseases and mainly in cancer this balance is lost due to mutations or over-activation of upstream pathways leading to persistent proliferation and tumor growth. What makes mTOR attractive to researchers seems to be its key position which is at the crossroads of various signal pathways (Ras,PI3K/Akt,TSC,NF-κB) towards mRNA,ribosome,protein synthesis and translation of significant molecules,the uncontrolled production of which may lead to tumor proliferation and growth. Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin (a natural product) or its analogs aims to prevent deleterious effects of abnormal signaling,regardless of which point of the signal pathway the abnormality has launched (78, 79). The mTOR pathway is activated in cervical carcinomas. Temsirolimus is the sole mTOR inhibitor to be evaluated in patients with cervical cancer.

Temsirolimus

The phase Ⅱ study assessed the activity of the mTOR inhibitor,temsirolimus,in patients with measurable metastatic and/or locally advanced,recurrent carcinoma of the cervix. Temsirolimus 25 mg i.v. was administered weekly in 4-week cycles (80).

Thirty-eight patients were enrolled. Thirty-seven patients were evaluable for toxicity and 33 for response. One patient experienced a PR (3.0%). Nineteen patients had SD (57.6%) [median duration 6.5 months (rage,2.4-12.0 months)]. The 6-month PFS rate was 28% (95% CI,14-43%). The median PFS was 3.52 months (95% CI,1.81-4.70). Assessment of PTEN and PIK3CA by IHC,copy number analyses and PTEN promoter methylation status did not reveal subsets associated with disease stability.

In this study,one patient experienced a PR and 58% had SD as the best response. The median duration of SD (6.5 months) is comparable to that seen with anti-angiogenic agents such as bevacizumab (3.5 months) in similar patients’ population. They conclude that single agent temsirolimus has modest activity in cervical carcinoma in about 2/3 of patients exhibiting SD.

Supportive care based treatment strategies

In the last section,we analyzed the effectiveness,cost,and QOL associated with both current and novel treatment strategies for patients with recurrent cancer.

Despite the poor response of recurrent cervical cancer to chemotherapy,treatment usually consists of aggressive chemotherapy regimens with substantial toxicity and decreased QOL,raising the question of whether or not this strategy is cost-effective (81, 82).

Moore and colleagues analyzed data from three separate GOG trials evaluating cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens for recurrent cervical cancer and identified five poor prognostic factors significantly and independently associated with reduced OS (GOG performance status 1 or 2,pelvic recurrence,prior radio-sensitizing chemotherapy,African American race,and first recurrence within 1 year of diagnosis) (82). When four or more of these poor prognostic factors exist together,patients are at the highest risk for treatment failure (16% of patients in the analysis by Moore and colleagues) and have the poorest prognosis with OS of less than 6 months,even with aggressive combination cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Recurrent cervical cancer is generally considered incurable and current chemotherapy regiments offer only modest gains in OS,particularly for patients with multiple poor prognostic factors.

Phippen et al. explored using decision analysis of effectiveness,cost,and QOL associated with both current and novel treatment strategies for patients with recurrent cancer (83).

Their model is designed to identify both the most effective and cost-effective among four modeled strategies for managing recurrent cervical cancer: (I) standard (cisplatin-containing) doublet chemotherapy for all patients; (Ⅱ) selective chemotherapy (home hospice with no chemotherapy for poorest prognosis patients with remainder receiving standard doublet chemotherapy); (Ⅲ) single agent chemotherapy with home hospice; and (IV) home hospice care for all patients (no chemotherapy).

Survival in selective chemotherapy strategy was 8.7 months overall,which is an incidence-based representation of the estimated survival rates of the arms of two subgroups,according to the Moore et al. study: the poorest prognosis patients (16%) receiving home hospice (OS,3.3 months) with the remainder (84%) receiving standard doublet chemotherapy (OS,9.7 months) (84).

Standard doublet chemotherapy for all is not cost-effective compared to selective chemotherapy with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $276,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Sensitivity analysis predicted that a 90% improvement in survival is required before standard doublet chemotherapy is cost-effective in poorest prognosis patients.

Selective chemotherapy is the most cost-effective strategy compared to single-agent chemotherapy with home hospice with an ICER of $78,000/QALY. Chemotherapy containing regimens become cost-prohibitive with small decrease in QOL.

GOG240 reported a 4-month (22%) improvement in OS when bevacizumab is added to platinum-based doublet chemotherapy (56). However,the costs associated with bevacizumab are substantial and the gains seen with the addition of bevacizumab in other cancer types have yet to prove cost-effective (83, 84, 85, 86). Supportive care based treatment strategies are potentially more cost-effective than the current standard of doublet chemotherapy for all patients with recurrent cervical cancer and warrant prospective evaluation.

Conclusions

Since cisplatin was considered as the historical standard treatment for recurrent cervical cancer,subsequent trials have evaluated and demonstrated activity with other agents. The results of GOG204 paclitaxel/cisplatin is considered to be the current recommended regimen for recurrent cervical cancer patients. Also,JCOG0505 in a secondary analysis revealed that for patients who had not received prior platinum,the cisplatin/paclitaxel appeared to be superior to carboplatin/paclitaxel with median OS. Without evidence of inferiority,carboplatin/paclitaxel may become the new standard for patients with recurrent disease,unless they have not received prior chemoradiation therapy,where they may benefit from cisplatin/paclitaxel. Although,the prognosis for recurrent cervical cancer patients is still poor,the results of GOG240 shed light on the usefulness of molecular target agents to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Recurrent cervical cancer is generally considered incurable and current chemotherapy regiments offer only modest gains in OS,particularly for patients with multiple poor prognostic factors. Therefore,it is crucial to consider not only the survival benefit,but also the minimization of treatment toxicity,and maximization of QOL.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Gustafsson L, Ponten J, Zack M, et al. International incidence rates of invasive cervical cancer after introduction of cytological screening. Cancer Causes Control 1997;8:755-63. [PubMed]

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69-90. [PubMed]

- Monk BJ, Tewari KS, Koh WJ. Multimodality therapy for locally advanced cervical carcinoma: state of the art and future directions. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2952-65. [PubMed]

- Tewari KS. Expert panel: patients with metastatic/recurrent cervical cancer should be treated with cisplatin plus paclitaxel. Clin Ovarian Cancer 2011;4:90-3.

- Monk BJ, Sill MW, McMeekin DS, et al. Phase Ⅲ trial of four cisplatin-containing doublet combinations in stage ⅣB, recurrent, or persistent cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4649-55. [PubMed]

- Tewari KS. A critical need for reappraisal of therapeutic options for women with metastatic and recurrent cervical carcinoma: commentary on Gynecologic Oncology Group protocol 204. Am J Hematol Oncol 2010;9:31-4. [PubMed]

- Tewari KS, Monk BJ. The rationale for the use of non-platinum chemotherapy doublets for metastatic and recurrent cervical carcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2010;8:108-15. [PubMed]

- Tewari KS, Monk BJ. Gynecologic oncology group trials of chemotherapy for metastatic and recurrent cervical cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2005;7:419-34. [PubMed]

- Bonomi P, Blessing JA, Stehman FB, et al. Randomized trial of three cisplatin dose schedules in squamous-cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1985;3:1079-85. [PubMed]

- Thigpen JT, Blessing JA, DiSaia PJ, et al. A randomized comparison of a rapid versus prolonged (24 hr) infusion of cisplatin in therapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 1989;32:198-202. [PubMed]

- McGuire WP Ⅲ, Arseneau J, Blessing JA, et al. A randomized comparative trial of carboplatin and iproplatin in advanced squamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1462-8. [PubMed]

- Omura GA, Blessing JA, Vaccarello L, et al. Randomized trial of cisplatin versus cisplatin plus mitolactol versus cisplatin plus ifosfamide in advanced squamous carcinoma of the cervix: a GynecologicOncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:165-71. [PubMed]

- Bloss JD, Blessing JA, Behrens BC, et al. Randomized trial of cisplatin and ifosfamide with or without bleomycin in squamous carcinoma of the cervix: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1832-7. [PubMed]

- Moore DH, Blessing JA, McQuellon RP, et al. Phase Ⅲ study of cisplatin with or without paclitaxel in stage ⅣB, recurrent, or persistent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3113-9. [PubMed]

- Long HJ Ⅲ, Bundy BN, Grendys EC Jr, et al. Randomized phase Ⅲ trial of cisplatin with or without topotecan in carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:4626-33. [PubMed]

- Moore DH, Tian C, Monk BJ, et al. Prognostic factors for response to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2010;116:44-9. [PubMed]

- Tewari KS, Monk BJ. Recent achievements and future developments in advanced and recurrent cervical cancer: trials of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Semin Oncol 2009;36:170-80. [PubMed]

- Rose PG, Java J, Whitney CW, et al. Nomograms predicting progression-free survival, overall survival, and pelvic recurrence in locally advanced cervical cancer developed from an analysis of identifiable prognostic factors in patients from NRG oncology/gynecologic oncology group randomized trials of chemoradiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2136-42. [PubMed]

- Greer BE, Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, et al. Cervical cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:1388-416. [PubMed]

- DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT. Clinical gynecologic oncology, 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002.

- Thigpen T, Shingleton H, Homesley H, et al. Cis-platinum in treatment of advanced or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a phase Ⅱ study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Cancer 1981;48:899-903. [PubMed]

- Hsiang YH, Liu LF. Identification of mammalian DNA topoisomerase I as intracellular targets of the anticancer drug camptothecin. Cancer Res 1988;48:1722-6. [PubMed]

- Chou TC, Motzer RJ, Tong Y, et al. Computerized quantitation of synergism and antagonism of taxol, topotecan, and cisplatin against human teratocarcinoma cell growth: a rational approach to clinical protocol design. J. Natl Cancer Inst 1994;86:1517-24. [PubMed]

- Bookman MA, Blessing JA, Hanjani P, et al. Topotecan in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a phase Ⅱ study of the gynecologic oncology group. Gynecol Oncol 2000;77:446-9. [PubMed]

- Curtin JP, Blessing JA, Webster KD, et al. Paclitaxel, an active agent in nonsquamous carcinomas of the uterine cervix: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1275-8. [PubMed]

- Gradishar WJ. Albumin-bound paclitaxel: a next-generation taxane. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2006;7:1041-53. [PubMed]

- Micha JP, Goldstein BH, Birk CL, et al. Abraxane in the treatment of ovarian cancer: the absence of hypersensitivity reactions. Gynecol Oncol 2006;100:437-8. [PubMed]

- Gradishar WJ, Krasnojan D, Cheporov S, et al. Significantly longer progression-free survival with nab-paclitaxel compared with docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3611-9. [PubMed]

- Rose PG, Blessing JA, Arseneau J. Phase Ⅱ evaluation of altretamine for advanced and recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 1996;62:100-2. [PubMed]

- Rose PG, Blessing JA, Morgan M, et al. Prolonged oral etoposide in recurrent or advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 1998;70:263-6. [PubMed]

- Schilder RJ, Blessing JA, Morgan M, et al. Evaluation of gemcitabine in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Phase Ⅱ study of the gynecologic oncology group. Gynecol Oncol 2000;76:204-7. [PubMed]

- Monk BJ, Sill MW, Burger RA, et al. Phase Ⅱ trial of Bevacizumab in the treatment of persistent or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1069-74. [PubMed]

- Thigpen T. The role of chemotherapy in the management of carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer J 2003;9:425-32. [PubMed]

- Weiss GR, Green S, Hannigan EV, et al. A phase Ⅱtrial of carboplatin for recurrent or metastatic squamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 1990;39:332-6. [PubMed]

- Noda K, Ikeda M, Yakushiji M, et al. A phase Ⅱ clinical study of cis-diammine glycolato platinum, 254-S, for cervical cancer of the uterus. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1992;19:885-92. [PubMed]

- Kato T, Nishimura H, Yakushiji M, et al. Phase Ⅱ study of 254-S(cis-diammine glycolato platinum) for gynecological cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1992;19:695-701. [PubMed]

- McGuire WP, Blessing JA, Moore D, et al. Paclitaxel has moderate activity in squamous cervix cancer. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:792-5. [PubMed]

- Takeuchi S, Dobashi K, Fujimoto S, et al. A late phase Ⅱ study of CPT-11 on uterine cervical cancer and ovarian cancer. Research Groups of CPT-11 in Gynecologic Cancers. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1991;18:1681-9. [PubMed]

- Look KY, Blessing JA, Muss HB, et al. 5-fluorouracil and low-dose leucovorin in the treatment of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. A phase Ⅱ trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1992;15:497-9. [PubMed]

- Look KY, Blessing JA, Gallup DG, et al. A phase Ⅱ trial of 5-fluorouracil and high-dose leucovorin in patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am J Clin Oncol 1996;19:439-41. [PubMed]

- Wasserman TH, Carter SK. The integration of chemotherapy into combined modality treatment of solid tumors. VⅢ. Cervical cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 1977;4:25-46. [PubMed]

- Lhommé C, Vermorken JB, Mickiewicz E, et al. Phase Ⅱ trial of vinorelbine in patients with advanced and/or recurrent cervical carcinoma: an EORTC Gynaecological Cancer Cooperative Group Study. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:194-9. [PubMed]

- Garcia AA, Blessing JA, Vaccarello L, et al. Phase Ⅱ clinical trial of docetaxel in refractory squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am J Clin Oncol 2007;30:428-31. [PubMed]

- Rose PG, Blessing JA, Lele S, et al. Evaluation of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin(Doxil)as seconddndin chemotherapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a phase Ⅱ study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2006;102:210-3. [PubMed]

- Fiorica J, Holloway R, Ndubisi B, et al. Phase Ⅱ trial of topotecan and cisplatin in persistent or recurrent squamous and nonsquamous carcinomas of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol 2002;85:89-94. [PubMed]

- Rose PG, Blessing JA, Gershenson DM, et al. Paclitaxel and cisplatin as first-line therapy in recurrent or advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2676-80. [PubMed]

- Tinker AV, Bhagat K, Swenerton KD, et al. Carboplatin and paclitaxel for advanced and recurrent cervical carcinoma: the British Columbia Cancer Agency experience. Gynecol Oncol 2005;98:54-8. [PubMed]

- Papadimitriou CA, Sarris K, Moulopoulos LA, et al. Phase Ⅱ trial of paclitaxel and cisplatin in metastatic and recurrent carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:761-6. [PubMed]

- Sutton GP, Blessing JA, Adcock L, et al. Phase Ⅱ study of ifosfamide and mesna in patients with previously-treated carcinoma of the cervix. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Invest New Drugs 1989;7:341-3. [PubMed]

- Schilder RJ, Blessing J, Cohn DE. Evaluation of gemcitabine in previously treated patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a phase Ⅱ study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2005;96:103-7. [PubMed]

- Muderspach LI, Blessing JA, Levenback C, et al. A Phase Ⅱ study of topotecan in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2001;81:213-5. [PubMed]

- Muggia FM, Blessing JA, Method M, et al. Evaluation of vinorelbine in persistent or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2004;92:639-43. [PubMed]

- Muggia FM, Blessing JA, Waggoner S, et al. Evaluation of vinorelbine in persistent or recurrent nonsquamous carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2005;96:108-11. [PubMed]

- Morris M, Blessing JA, Monk BJ, et al. Phase Ⅱ study of cisplatin and vinorelbine in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3340-4. [PubMed]

- Stehman FB, Blessing JA, McGehee R, et al. A phase Ⅱ evaluation of mitolactol in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1892-5. [PubMed]

- Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ 3rd, et al. Improved survival with bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;370:734-43. [PubMed]

- Kitagawa R, Katsumata K, Shibata T, et al. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus paclitaxel plus cisplatin in metastatic or recurrent cervical cancer: The Open-Label Randomized Phase Ⅲ Trial (JCOG0505). J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2129-35. [PubMed]

- Yaegashi N, Ito K, Niikura H, et al. Treatment Guidelines for Cervical Cancer 2011 Edition (Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology). Avialble online: http://jsgo.or.jp/guideline/img/keigan2011-06.pdf

- Rahimi N. The ubiquitin-proteasome system meets angiogenesis. Mol Cancer Ther 2012;11:538-48. [PubMed]

- Wahl O, Oswald M, Tretzel L, et al. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by antibodies, synthetic small molecules and natural products. Curr Med Chem 2011;18:3136-55. [PubMed]

- Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med 1971;285:1182-6. [PubMed]

- Gasparini G. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer. Oncologist 2000;5 Suppl 1:37-44. [PubMed]

- Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev 2004;25:581-611. [PubMed]

- Cheng WF, Chen CA, Lee CN, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and prognosis of cervical carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:721-6. [PubMed]

- Lee CM, Shrieve DC, Zempolich KA, et al. Correlation between human epidermal growth factor receptor family (EGFR, HER2, HER3, HER4), phosphorylated Akt (P-Akt), and clinical outcomes after radiation therapy in carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol 2005;99:415-21. [PubMed]

- Loncaster JA, Cooper RA, Logue JP, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression is a prognostic factor for radiotherapy outcome in advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Br J Cancer 2000;83:620-5. [PubMed]

- Guidi AJ, Abu-Jawdeh G, Berse B, et al. Vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) expression and angiogenesis in cervical neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:1237-45. [PubMed]

- Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, et al. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004;3:391-400. [PubMed]

- Presta LG, Chen H, O'Connor SJ, et al. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res 1997;57:4593-9. [PubMed]

- Monk BJ, Mas Lopez L, Zarba JJ, et al. Phase Ⅱ, open-label study of pazopanib or lapatinib monotherapy compared with pazopanib plus lapatinib combination therapy in patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3562-9. [PubMed]

- Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase Ⅲ trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1061-8. [PubMed]

- Monk BJ, Mas Lopez L, Zarba JJ, et al. Phase Ⅱ, open-label study of pazopanib or lapatinib monotherapy compared with pazopanib plus lapatinib combination therapy in patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3562-9. [PubMed]

- Monk BJ, Pandite LN. Survival data from a phase Ⅱ, open-label study of pazopanib or lapatinib monotherapy in patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4845. [PubMed]

- Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, et al. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1995;19:183-232. [PubMed]

- Herbst RS, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib-a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:956-65. [PubMed]

- Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multiinstitutional randomized phase Ⅱ trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial)[corrected]. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2237-46. [PubMed]

- Goncalves A, Fabbro M, Lhomme C, et al. A phase Ⅱ trial to evaluate gefitinib as second- or third-line treatment in patients with recurring locoregionally advanced or metastatic cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2008;108:42-6. [PubMed]

- Strimpakos AS, Karapanagiotou EM, Saif MW, et al. The role of mTOR in the management of solid tumors: an overview. Cancer Treat Rev 2009;35:148-59. [PubMed]

- Lang SA, Gaumann A, Koehl GE, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin is activated in human gastric cancer and serves as a target for therapy in an experimental model. Int J Cancer 2007;120:1803-10. [PubMed]

- Tinker AV, Ellard S, Welch S, et al. Phase Ⅱ study of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in women with recurrent, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic carcinoma of the cervix. A trial of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG IND 199). Gynecol Oncol 2013;130:269-74. [PubMed]

- de Kok IM, Polder JJ, Habbema JD, et al. The impact of healthcare costs in the last year of life and in all life years gained on the cost-effectiveness of cancer screening. Br J Cancer 2009;100:1240-4. [PubMed]

- Moore KN, Rowland MR. Treatment Advances in Locoregion-ally Advanced and Stage ⅣB/Recurrent Cervical Cancer: Can We Agree That More Is Not Always Better? J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2125-8. [PubMed]

- Phippen NT, Leath CA 3rd, Miller CR, et al. Are supportive care-based treatment strategies preferable to standard chemotherapy in recurrent cervical cancer? Gynecol Oncol 2013;130:317-22. [PubMed]

- Moore DH, Tian C, Monk BJ, et al. Prognostic factors for response to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol Jan 2010;116:44-9.

- Cohn DE, Kim KH, Resnick KE, et al. At what cost does a potential survival advantage of bevacizumab make sense for the primary treatment of ovarian cancer? A cost-effectiveness analysis. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1247-51. [PubMed]

- Goulart B, Ramsey S. A trial-based assessment of the cost-utility of bevacizumab and chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Value Health 2011;14:836-45. [PubMed]