DNA image cytometry test for primary screening of esophageal cancer: a population-based multi-center study in high-risk areas in China

Meng Wang1, Changqing Hao2, Qing Ma1, Guohui Song3, Shanrui Ma1, Deli Zhao4, Lin Zhao5, Xinqing Li1, Wenqiang Wei1

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the feasibility of DNA image cytometry (DNA-ICM) as a primary screening method for esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC).

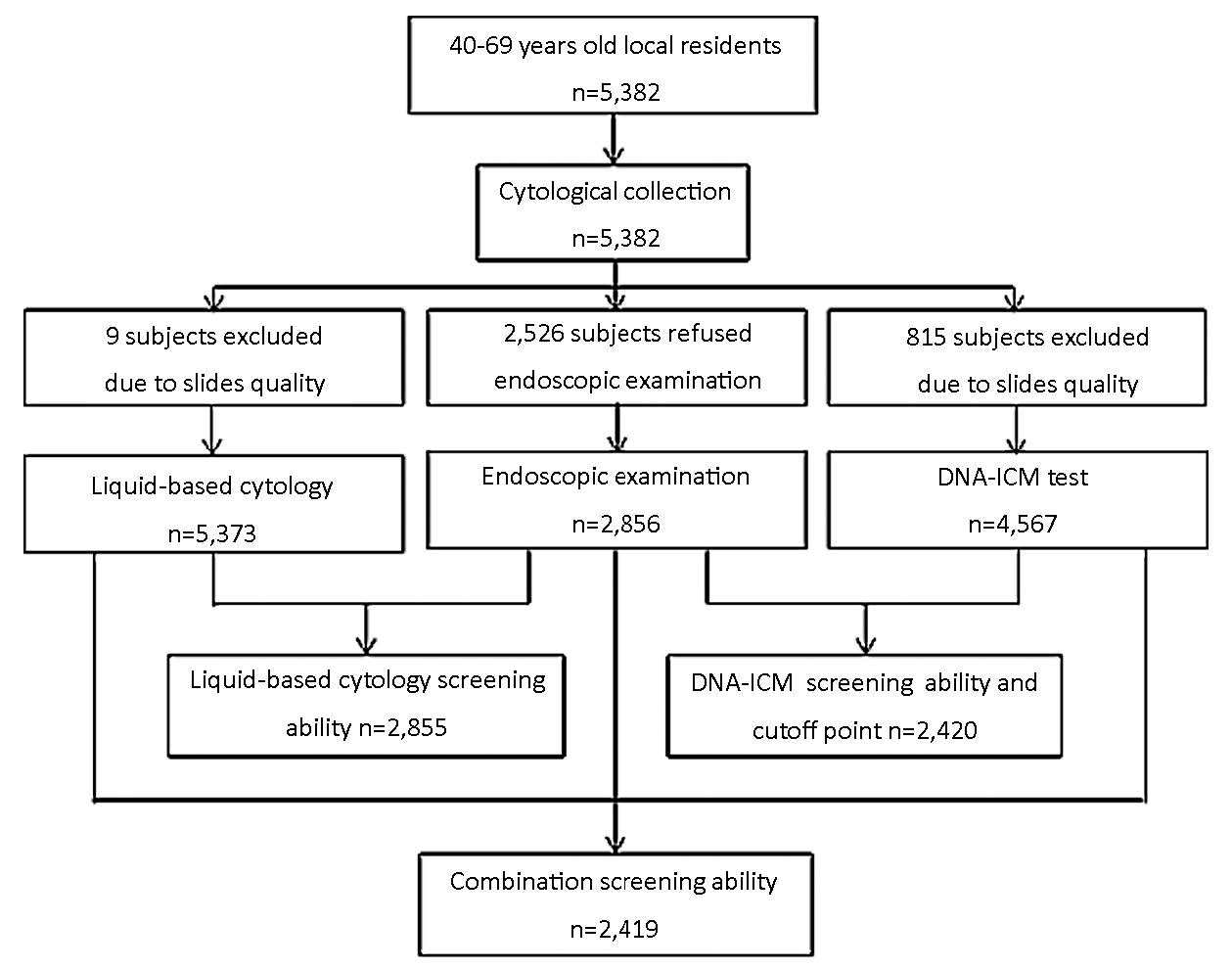

Methods: A total of 5,382 local residents aged 40–69 years from three high-risk areas in China (Linzhou in Henan province, Feicheng in Shandong province and Cixian in Hebei province) from 2008 to 2011 were recruited in this population-based screening study. And 2,526 subjects declined to receive endoscopic biopsy examination with Lugol’s iodine staining, while 9 and 815 subjects were excluded from liquid-based cytology and DNA-ICM test respectively due to slide quality. Finally, 2,856, 5,373 and 4,567 subjects were enrolled in the analysis for endoscopic biopsy examination, liquid-based cytology and DNA-ICM test, respectively. Sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), negative predictive values (NPV) and positive predictive values (PPV) as well as their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for DNA-ICM, liquid-based cytology and the combination of the two methods were calculated. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were applied to determine the cutoff point of DNA-ICM for esophageal cancer.

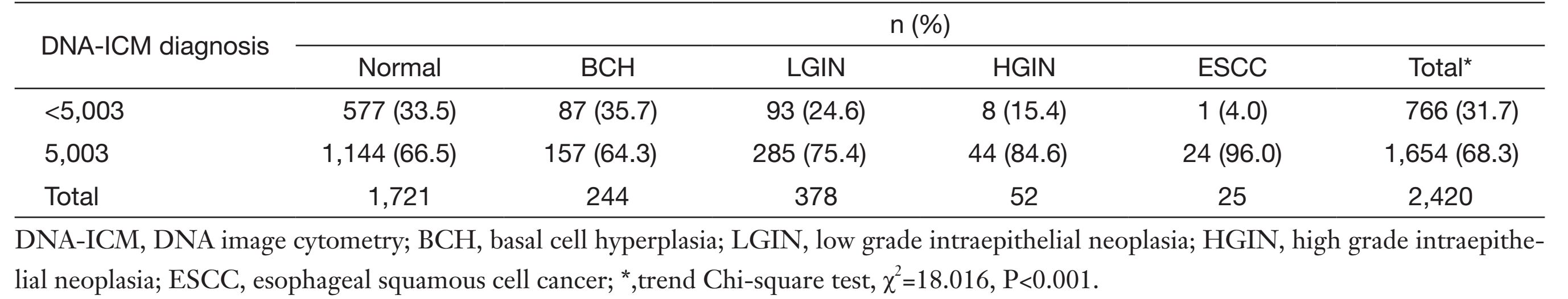

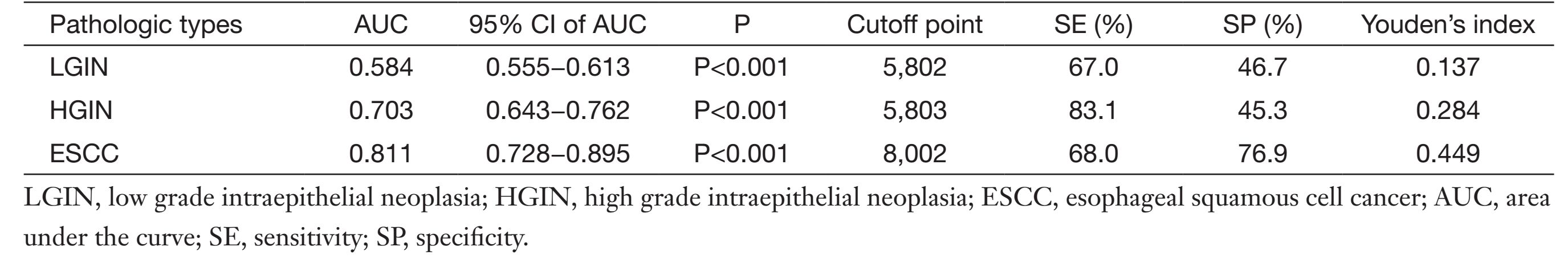

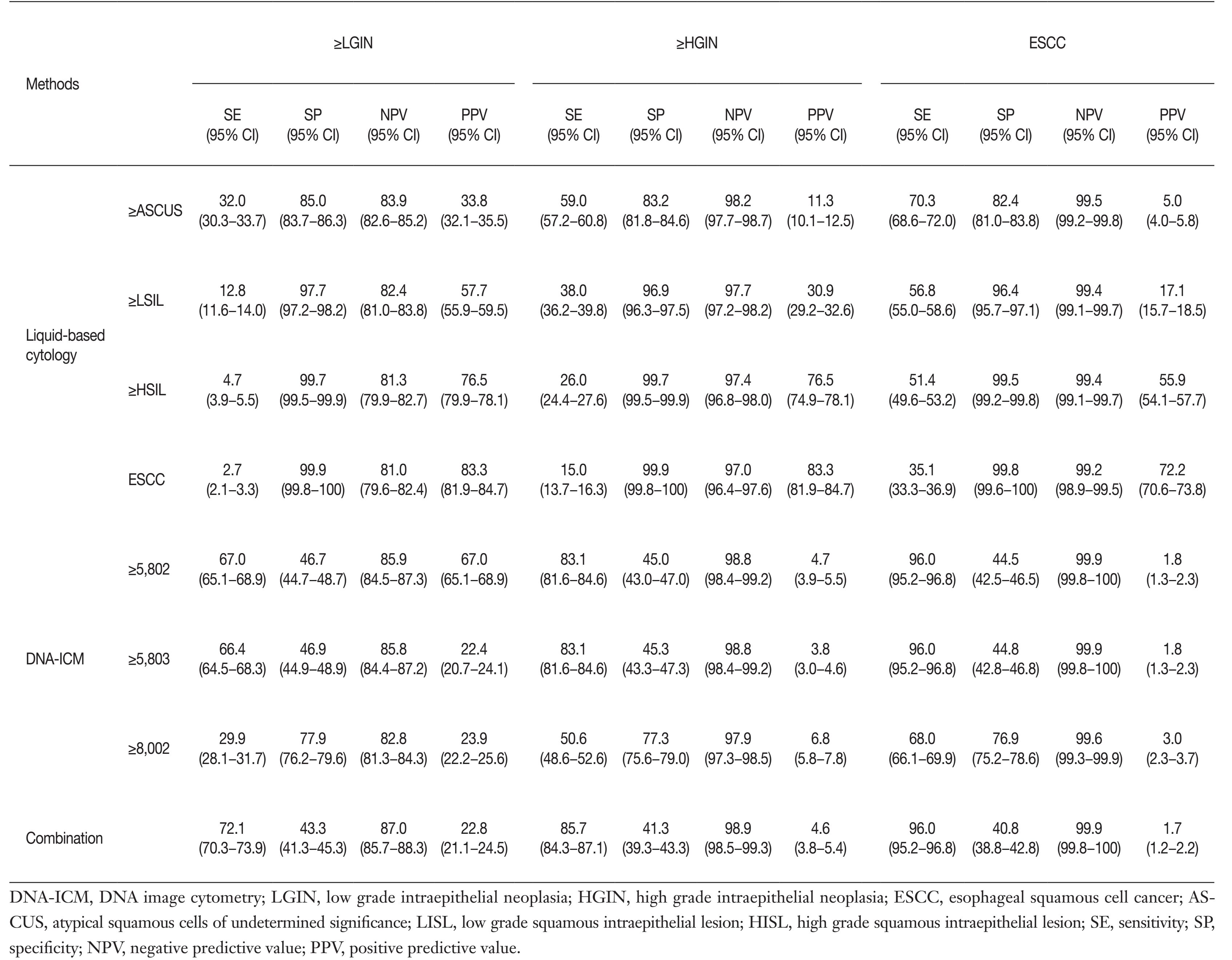

Results: DNA-ICM results were significantly correlative with esophageal cancer and precancer lesions (χ2=18.016, P<0.001). The cutoff points were 5,802, 5,803 and 8,002 based on dissimilar pathological types of low grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN), high grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN), and ESCC, respectively, and 5,803 was chosen in this study considering the SE and SP. The SE, SP, PPV, NPV of DNA-ICM test (cutoff point 5,803) combined with liquid-based cytology [threshold atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS)] were separately 72.1% (95% CI: 70.3%-73.9%), 43.3% (95% CI: 41.3%-45.3%), 22.8% (95% CI: 21.1%-24.5%) and 87.0% (95% CI: 85.7%-88.3%) for LGIN, 85.7% (95% CI: 84.3%-87.1%), 41.3% (95% CI: 39.3%-43.3%), 4.6% (95% CI: 3.8%-5.4%) and 98.9% (95% CI: 98.5%-99.3%) for HGIN, and 96.0% (95% CI: 95.2%-96.8%), 40.8% (95% CI: 38.8%-42.8%), 1.7% (95% CI: 1.2%-2.2%) and 99.9% (95% CI: 99.8%-100.0%) for ESCC.

Conclusions: It is possible to use DNA-ICM test as a primary screening method before endoscopic screening for esophageal cancer.

Keywords: DNA image cytometry; esophageal cancer; cutoff point

Submitted Sep 21, 2015. Accepted for publication May 02, 2016.

doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2016.04.03

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide and the sixth most common cause of death of all cancers, over 80% of which occur in less developed regions (1). In China, the incidence and mortality of esophageal cancer are 14.73/100, 000 and 10.62/100, 000 respectively in 2012, with incidence rates about twofold higher than that in the world (2). Esophageal cancer has a poor survival since patients in early stages are asymptomatic and usually diagnosed at the advanced stage (3). Screening, therefore, is the key for detecting patients before they are advanced.

Several screening methods have been launched in high-risk areas of China since 1970s, including conventional cytology (4-7), liquid-based cytology (8), occult blood detection (9) and endoscopic biopsy examination with Lugol’s iodine staining (10-13). At present, endoscopic biopsy examination with Lugol’s iodine staining, being most commonly conducted in China due to high sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP), has been proved to significantly reduce accumulative incidence and mortality in high risk areas by a ten-year follow-up study (12). However, high expenditure and skilled pathologists and endoscopic physicians are required, which makes endoscopic screening not appropriate in the whole population (14, 15). As a result, some convenient and economical primary screening approaches are needed before performing endoscopic examination.

DNA image cytometry (DNA-ICM) has been applied as a mass screening method to cervical cancer and is shown to obtain a higher SE than cytology (16). To our knowledge, there are limited studies on DNA-ICM for large-scale esophageal cancer screening. Our research team has tried to explore the DNA-ICM in a population-based study of 582 subjects in Linzhou and Feicheng and proved that this technique has the potential to be a primary screening method (17). On the basis of previous research, we enlarge the population to further evaluate the feasibility of DNA-ICM as a primary screening method for esophageal cancer and determine the cutoff point for esophageal cancer diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Study design and subjects recruitment

This was a population-based screening study, with 5, 382 subjects from three high-risk areas in China (Linzhou in Henan province, Feicheng in Shandong province and Cixian in Hebei province) from 2008 to 2011. Inclusion criteria were: 1) local residents; 2) aged 40-69 years; 3) no contraindications for endoscopic examinations (e.g. history of reaction to iodine or lidocaine, serious cardiovascular disease, poor health status); and 4) voluntarily consenting to participate in screening and signing the informed consent document. Exclusion criteria were: participants who had a history of liver cirrhosis, esophageal varices, hematemesis, a bleeding disorder, uncontrolled congestive heart failure, unstable angina or a reaction to topical anesthetics or iodine. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Cancer Institute/Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CICAMS) and Peking Union Medical College. The details of subject recruitment and exclusion and the study procedure are described in our previous study (12).

Endoscopic screening and cytological test sample collection

Endoscopic screening was completed by local doctors after training and under the supervision of experienced doctors from the CICAMS. The technical processes of endoscopic screening and the requirements of follow-up after screening have been described at length in our former research (17). The biopsy slides were read blindly by two experienced pathologists without knowledge of the visual endoscopic results. The pathologic results were classed as normal, basal cell hyperplasia (BCH), low grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN), high grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN) and esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC).

Balloon examination was performed by an experienced local doctor to collect cytological samples. Then each sample was divided into two slides and stained randomly by a Pap smear or Feulgen method respectively. The former was used for liquid-based cytological study and the latter was employed to DNA-ICM test. The detailed procedures of sample collection, specimens’ preparation were in our previous study (17). The cytological slides were reviewed by two cytopathologists independently, and discrepancies were adjudicated by joint review. The slides were read blindly without the pathological results. The diagnostic criteria for cytological study were normal, benign reactive cellular changes (BCC), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LISL), high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HISL) and ESCC.

The DNA-ICM specimens were read by hard ware systems, including a MOTIC BA600 microscope, DELL370 workstation, automated microscope control-box, Moticam 1501 camera and assistant accessories. Our preceding study had amply depicted the operation principles of the system and the conventional result expression method by the content of DNA ploidy and the number of aneuploidy cells (17). Based on the former method, we gave every subject who had DNA-ICM test a 4-digit code, which combined the content of DNA ploidy and the number of aneuploidy cells together, and which represented the health condition of each subject. The first two digits meant the maximum DNA ploidy content and the rest two digits accounted for the number of the maximum DNA ploidy content cells. For example, if the maximum DNA ploidy content was 7.5c and the amount of this kind of cell was 22, the 4-digit number was 7, 522. The larger the 4-digit code, the more serious the subject’s DNA-ICM result.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were done using SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Demographic, pathologic and cytological outcomes were compared by χ2 test. The correlation between DNA-ICM results and esophageal cancer and precancerous lesions is evaluated by trend test. SE, SP, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), as well as 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to indicate the screening ability of DNA-ICM, cytology and the combination of the two methods. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were applied to determine the cutoff point of DNA-ICM for esophageal cancer, where lay the maximum Youden’s index. The statistical significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

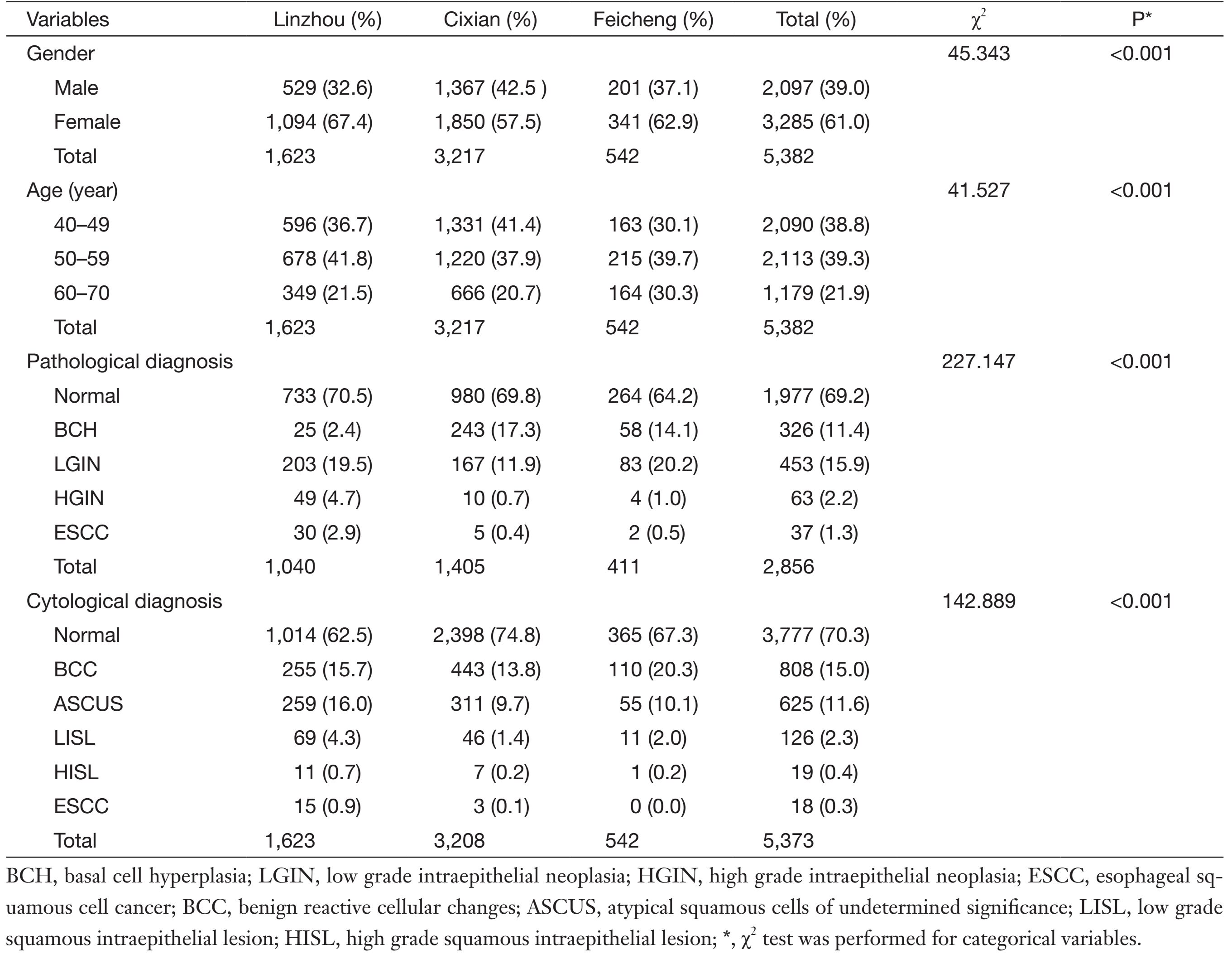

A total of 5, 382 local residents aged 40-69 years from Linzhou in Henan province, Cixian in Hebei province and Feicheng in Shandong province were enrolled in the study. The mean age of all participants was 52.7 years (range, 40-69 years) and females accounted for 61% (Table 1). Significant differences were observed among the three groups in both gender and age. The database for analysis was limited to various amounts of subject considering different aims. The detailed information is shown in Figure 1.

Full table

Pathologic examination

A total of 2, 856 of the 5, 382 subjects received endoscopic screening and pathological examination. The compliance was about 53.07%. The detection rate of esophageal lesions was about 31% both in different areas and in all participants. The detection rates from high to low were respectively LGIN, BCH, HGIN and ESCC, except for Linzhou, whose detection rate of BCH (2.4%) was even lower than ESCC (2.9%). The distribution of pathologic types was dissimilar significantly among the three areas (χ2=227.147, P<0.001) (Table 1).

Liquid-based cytology

All participants received balloon examination and had cytological samples, 9 of which were excluded due to slide quality. The detection rates of esophageal lesions by liquid-based cytology from high to low were respectively BCC, ASCUS, LSIL, HSIL and ESCC. While the normal was about 70% in average (3, 777/5, 373, range: 62.5% to 74.8%) and BCC was about 15% (808/5, 373, range: 13.8% to 20.3%). The distribution of cytological types was discrepant apparently among the three areas (χ2=142.889, P<0.001) (Table 1).

DNA-ICM test

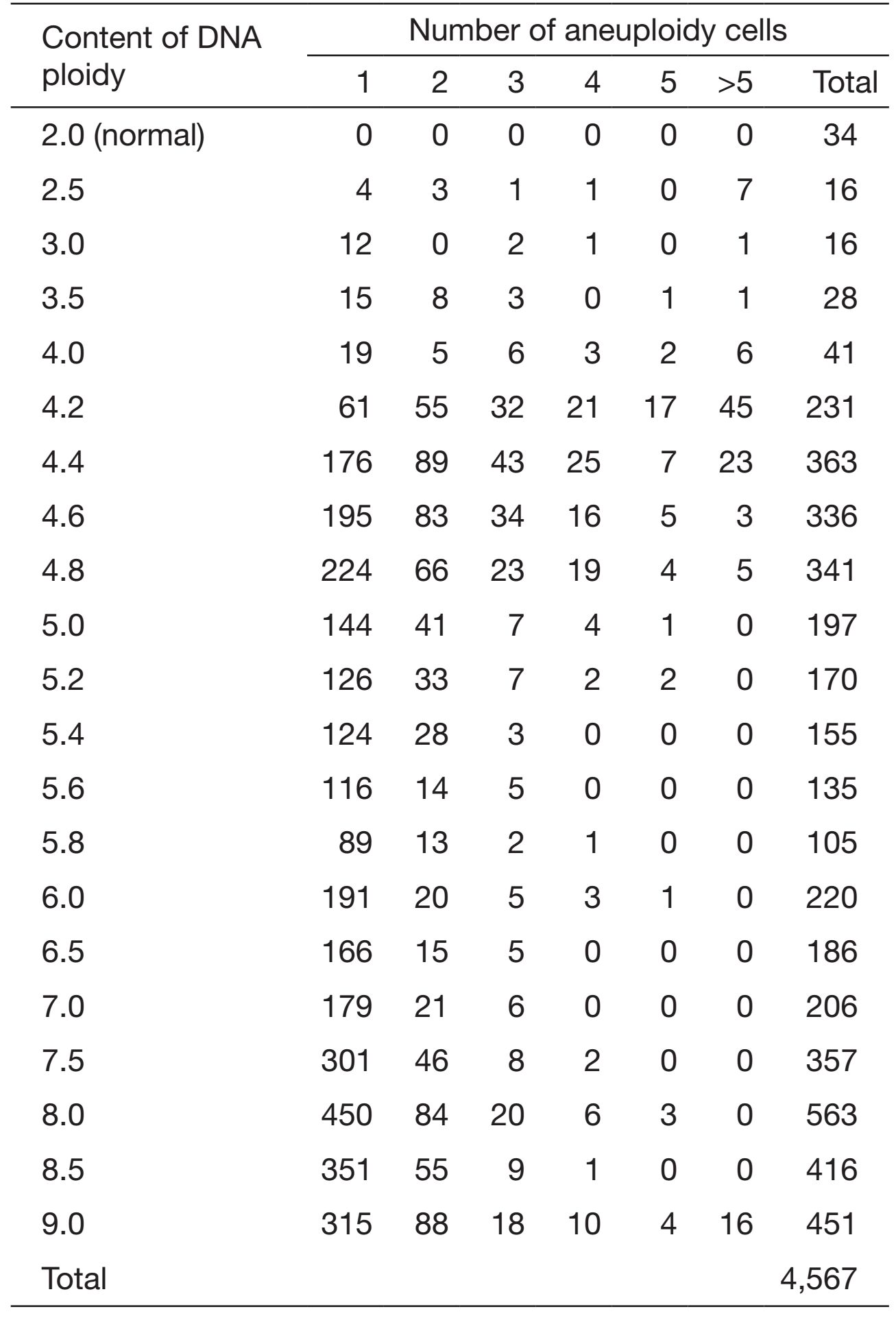

Same as liquid-based cytology, all participants had DNA-ICM test through balloon examination and 4, 567 cases were enrolled in the analysis because of high slide quality. Absolutely normal cells were few (0.74%, 34/4, 567), and the total quantity of aneuploidy cells ascended with content of DNA ploidy increasing at first until 4.8c. Then the amount aneuploidy cells dropped sharply to about 150 and went smoothly. The number rose up again from 6.5c and reached the peak at 8c (563) eventually. Using conventional cutoff point that the content of DNA ploidy 5c and the aneuploidy cells number 3, approximately 65.16% (2, 976/4, 567) subjects were diagnosed as abnormal (Table 2).

Full table

Distribution of DNA-ICM results based on various pathologic types

Conventional cutoff point (the content of DNA ploidy 5c and the aneuploidy cells number 3) was applied firstly to explore whether DNA-ICM test could be used for esophageal cancer primary screening. As shown in Table 3, with increasing pathologic grades, the abnormal group accounted for larger percentage (χ2=18.016, P<0.001). In esophageal cancer subjects, up to 96% cases could be found out by DNA-ICM test.

Full table

Cutoff points of DNA-ICM based on dissimilar pathologic types

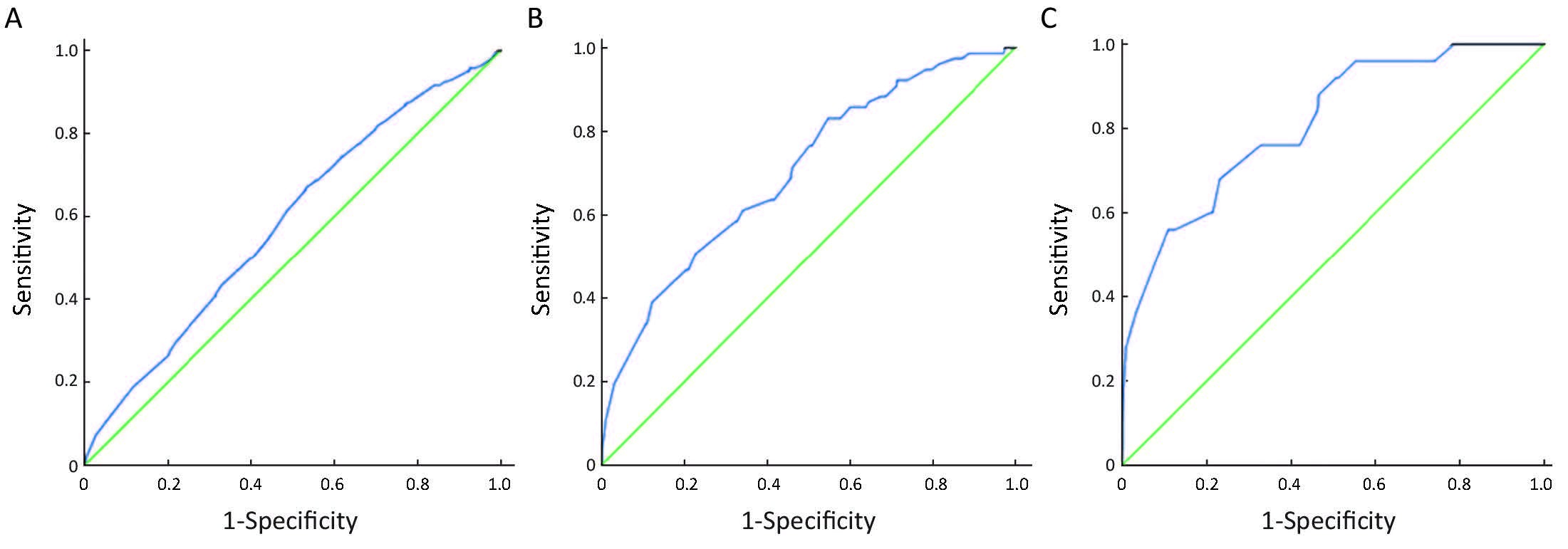

ROC curves were employed to illustrate cutoff point for DNA-ICM test. The area under the curves (AUCs) was 0.584, 0.703 and 0.811 respectively for pathologic types of LGIN, HGIN and ESCC. We further applied Youden’s index to confirm the cutoff point for each pathologic type. The cutoff points lay on the largest Youden’s index point of each ROC curve, which were 5, 802 for LGIN, 5, 803 for HGIN and 8, 002 for ESCC, namely, the content of DNA ploidy 5.8c and the aneuploidy cells number 3 were the appropriate cutoff points for HGIN, and the explanation for 5, 802 and 8, 002 was by analogy (Table 4, Figure 2).

Full table

Screening ability of liquid-based cytology and DNA-ICM test based on different pathologic types

When focusing on each kind of pathology results, the SE declined and SP rose in turn with higher grade of cytological or DNA-ICM classifications. In ≥HGIN, the SE dropped from 83.1% to 50.6%, while SP grew from 45.0% to 77.3%, when the result of DNA-ICM test changed from 5, 802 to 8, 002. What’s more, in each classification of liquid-based cytology or DNA-ICM, the SE increased significantly and the SP decreased smoothly when higher grade of pathologic types were used as classification criterion. With the classification of DNA-ICM being 5, 803, the SE went from 66.4% up to 96.0% when the pathologic classification criterion changed from ≥LGIN to ESCC. More importantly, the SE of DNA-ICM test was always higher than that of liquid-based cytology (Table 5).

Full table

SE and SP of combination of liquid-based cytology and DNA-ICM

In this study, ≥5, 803 of DNA-ICM test and ASCUS of liquid-based cytology were taken as threshold values for combination of the two methods to explore a better primary screening method. As shown in Table 5, the SE for HGIN was 85.7%, which was higher than both of the two methods alone. The same also happened in other pathologic classification criterions.

Discussion

Marked achievements had been made in esophageal cancer with endoscopic screening in China (12). Although high SE and SP had been proved (10, 11), some limitations, such as the relatively unacceptable cost and the necessity for experienced pathologists and endoscopic physicians, however, restricted the extension of endoscopic screening in China, especially in rural areas, where the most high-risk areas of esophageal cancer located. Therefore, the demand for some economic and easier primary screening methods before endoscopic screening with applicable SE emerged for asymptomatic population, which could not only narrow the population for endoscopic screening, but also enhance the screening efficiency, and thereby make it possible to promote endoscopic screening.

These days, an alternative method for examination of precancer lesions is DNA-ICM test. It is accepted worldwide, as a successful method in order to screen for epithelial dysplasia in situ or invasive carcinomas of the uteri cervix (16). The limited studies of DNA-ICM test on esophageal cancer focused on prognosis. Our team once discovered that DNA-ICM was suitable for esophageal cancer primary screening. But the cutoff point in that research was the conventional one and the sample size was deficient. To this end, based on the population cohort established in Lizhou, Cixian and Feicheng from 2008 to 2011, this study discussed the probability of DNA-ICM test for esophageal cancer screening and meanwhile explored the cutoff point for DNA-ICM test, with the gold standard of endoscopic biopsy examination with Lugol’s iodine staining. We further compared the method with liquid-based cytology and combined the two to investigate a primary screening approach for esophageal cancer and precancerous lesions. Besides, the content of DNA ploidy and the aneuploidy cells were united as one index to avoid the multiple biases resulted from various indexes.

The screening significance of DNA-ICM test in esophageal cancer is still controversial since few attempts have been made on this. Using the conventional classification of content of DNA ploidy 5c and the number of aneuploidy cells 3, we validated our previous study with a larger sample size. The data showed a strong correlation between DNA aneuploidy and increased risk of incidence (χ2=18.016, P<0.001), which was in agreement with the previous results (17) and proved it is possible that the DNA-ICM could be used for esophageal cancer screening.

No proper cutoff value was specially established for esophageal cancer screening before. In this study, LGIN, HGIN and ESCC were set respectively as the thresholds for golden standard of pathological examination (Table 4). Three ROC curves were then depicted based on different thresholds and the cutoff points were 5, 802, 5, 803 and 8, 002 for LGIN, HGIN and ESCC, which were chosen from the ROC curves where the Youden’s index was the highest. The cutoff point 5, 803, that was, the content of DNA ploidy 5.8c and the aneuploidy cells number 3, was ultimately defined as cutoff point for DNA-ICM test in our study on account of the following explanations. To begin with, the SE was too low for a primary screening method (22.9% for LGIN, 50.6% for ≥HGIN and 68.0% for ESCC), if 8, 002 was applied as the cutoff point. Secondly, the SE of 5, 802 and 5, 803 were practically the same no matter which pathologic threshold was and the SP of 5, 803 was a little higher than that of 5, 802. More importantly, it was the patients with pathologic results of HGIN that we cared about more, as patients diagnosed with HGIN or worse had little opportunity to reverse to LGIN or normal and treatment must be given to prolong their life-span and improve their living quality, which was the basic purpose for cancer screening (18).

The aim of primary screening was to find out suspicious cases as many as possible before endoscopic screening, and so the method with high SE was preferable. We compared the DNA-ICM test with liquid-based cytology and then combined the two methods to get the best way for esophageal cancer screening. As shown in Table 5, the SE of DNA-ICM test with threshold of ≥5, 803 (≥LGIN 66.4%, ≥HGIN 83.1% and ESCC 96.0%) was much higher than that of liquid-based cytology with threshold of ≥ASCUS (≥LGIN 32.0%, ≥HGIN 59.0% and ESCC 70.3%), which highlighted that the DNA-ICM was prior to liquid-based cytology for primary screening. We then united the two methods in the hope of achieving high SE, but the results were the opposite. The SE was improved little (≥LGIN 72.1%, ≥HGIN 85.7% and ESCC 96.0%), indicating that the combination was no better than DNA-ICM alone and was not suitable for screening ESCC and precancerous lesions, which was in accordance with our previous study.

Several superiorities make the DNA-ICM test a reasonable primary screening method. On the one hand, DNA-ICM test is easier to perform. Training for cytologists, endoscopists and pathologists for liquid-based cytology test or endoscopic screening is arduous and time-consuming, which restricts the application of the two methods to the entire population. However, for DNA-ICM test, a technician could work independently after 3 weeks of training, and 90% of slides could be diagnosed in one minute. On the other hand, cytological diagnosis largely depends on the experiences of cytologists, but DNA-ICM is more objective as it is read by computer (19). This might be a justifiable reason for various sensitivities of cancer screening. Our study also has some limitations. The quality of DNA-ICM specimens is supposed to be enhanced, since a total of 5, 382 subjects participated in DNA-ICM test, but only 4, 567 (84.86%) specimens were employed for analysis. Only when the quality is improved, will the method be possible to spread nationwide.

Conclusions

The cutoff point of DNA-ICM for primary screening of esophageal cancer was 5, 803, that is, the content of DNA ploidy 5.8c and the aneuploidy cells number 3. DNA-ICM test alone as a primary screening method possesses potential benefits in detecting esophageal cancer and its precursors with significantly high SE than liquid-based cytology.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledged the cooperation of all the stuffs in screening sites in providing cancer statistics, data collection, sorting, verification and database creation.

Funding: The research was granted by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81241091).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/ijc.29210

- Chen WQ, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, et al. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2012. Zhongguo Zhong Liu (in Chinese) 2016;25:1–8.

- Wang GQ, Jiao GG, Chang FB, et al. Long-term results of operation for 420 patients with early squamous cell esophageal carcinoma discovered by screening. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77:1740–4. [PubMed] DOI:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.098

- Shu YJ. Cytopathology of the esophagus. Acta Cytol 1983;27:7–16. [PubMed]

- Dawsey SM, Shen Q, Nieberg RK, et al. Studies of esophageal balloon cytology in Linxian, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997;6:121–30. [PubMed]

- Roth MJ, Liu SF, Dawsey SM, et al. Cytologic detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions using balloon and sponge samplers in asymptomatic adults in Linxian, China. Cancer 1997;80:2047–59. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142

- Shen O, Liu SF, Dawsey SM, et al. Cytologic screening for esophageal cancer: results from 12,877 subjects from a high-risk population in China. Int J Cancer 1993;54:185–8. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0215

- Pan QJ, Roth MJ, Guo HQ, et al. Cytologic detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and its precursor lesions using balloon samplers and liquid-based cytology in asymptomatic adults in Linxian, China. Acta Cytol 2008;52:14–23. [PubMed] DOI:10.1159/000325430

- Qin DX, Wang GQ, Yuan FL, et al. Screening for upper digestive tract cancer with an occult blood bead detector. Investigation of a normal north China population. Cancer 1988;62:1030–4. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142

- Dawsey SM, Lewin KJ, Liu FS, et al. Esophageal morphology from Linxian, China. Squamous histologic findings in 754 patients. Cancer 1994;73:2027–37. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142

- Dawsey SM, Wang GQ, Weinstein WM, et al. Squamous dysplasia and early esophageal cancer in the Linxian region of China: distinctive endoscopic lesions. Gastroenterology 1993;105:1333–40. [PubMed] DOI:10.1016/0016-5085(93)90137-2

- Wei WQ, Chen ZF, He YT, et al. Long-term follow-up of a community assignment, one-time endoscopic screening study of esophageal cancer in China. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1951–7. [PubMed] DOI:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.0423

- Dawsey SM, Fleischer DE, Wang GQ, et al. Mucosal iodine staining improves endoscopic visualization of squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Linxian, China. Cancer 1998;83:220–31. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142

- Roshandel G, Semnani S, Malekzadeh R. None-endoscopic screening for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-A review. Middle East J Dig Dis 2012;4:111–24.

- Kadri SR, Lao-Sirieix P, O’Donovan M, et al. Acceptability and accuracy of a non-endoscopic screening test for Barrett's oesophagus in primary care: cohort study. BMJ 2010;341:c4372. [PubMed] DOI:10.1136/bmj.c4372

- Tong H, Shen R, Wang Z, et al. DNA ploidy cytometry testing for cervical cancer screening in China (DNACIC Trial): a prospective randomized, controlled trial. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:6438–45. [PubMed] DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1689

- Zhao L, Wei WQ, Zhao DL, et al. Population-based study of DNA image cytometry as screening method for esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:375–82. [PubMed] DOI:10.3748/wjg.v18.i4.375

- Wang G. The trend and treatment for esophageal precancerous lesions. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi (in Chinese) 2002;24:206–7.

- Böcking A, Nguyen VQ. Diagnostic and prognostic use of DNA image cytometry in cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions and invasive carcinoma. Cancer 2004;102:41–54. [PubMed]